At the end of 2024, I was invited to attend the 5th International Conference on ED organised by the American Centre for Psychiatry and Neurology (ACPN) in Dubai. The speaker I was most excited about was Dr Cynthia Bulik, who has been researching the genetics of eating disorders for the past decade or so.

Dr Bulik is a living legend in the world of ED treatment. She published her first research paper in 1984 and has been working exclusively on ED ever since! She has held a number of senior positions in her career and is now Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill, as well as Professor of Nutrition at the Gillings School of Global Public Health. She is also the founding director of the University of North Carolina’s Centre of Excellence for Eating Disorders, as well as director of the Innovation Centre for ED at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden. Quite an authority in the field! Now you know why I wasn’t going to miss her presentation 😉

Dr Bulik’s research focuses on the treatment, epidemiology and molecular genetics of eating and body weight regulation disorders. She is actively involved in research both in the United States and in more than twenty countries around the world, including the Eating Disorder Genetic Initiative (EDGI), the largest-ever global study of the genetics of ED, which aims to identify the hundreds of genes that influence the risk of developing anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. Although social and cultural factors play a non-negligible role in the development of ED, recent research has revealed a substantial genetic influence.

Indeed, studies revealed that genetics account for 40-60% of the variability in Anorexia Nervosa, with the remainder being influenced by environmental factors.

At a time when social stigma and the perception that eating disorders are a ‘choice’ represent major barriers to the treatment of eating disorders, the EDGI uncovers the complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors that contribute to eating disorders, in order to improve diagnosis, management and treatment. Unravelling the genetic code of ED will pave the way for much-needed research and the development of new, more effective personalised treatments for these devastating diseases.

Last November, Dr Bulik came to talk about the results of the Genomewide-association study (GWAS), which compared the genetics of more than 17,000 people (that’s a huge sample!) suffering from anorexia nervosa and a 55,000 people control group in order to identify the parts of the genome that seem to increase the risk of anorexia, bulimia, hyperphagia and ARFID (Avoidant-Restrictive Food Intake Disorder).

The study identified several types of gene that differ between anorexic patients and the healthy population. What does this mean in concrete terms?

- Some genes seem to ‘increase the risk’ of developing anorexia nervosa.

- Genetics do play a role in anorexia nervosa

- – If continued overtime, this study should reveal up to several hundred genes correlated with the risk of developing ED

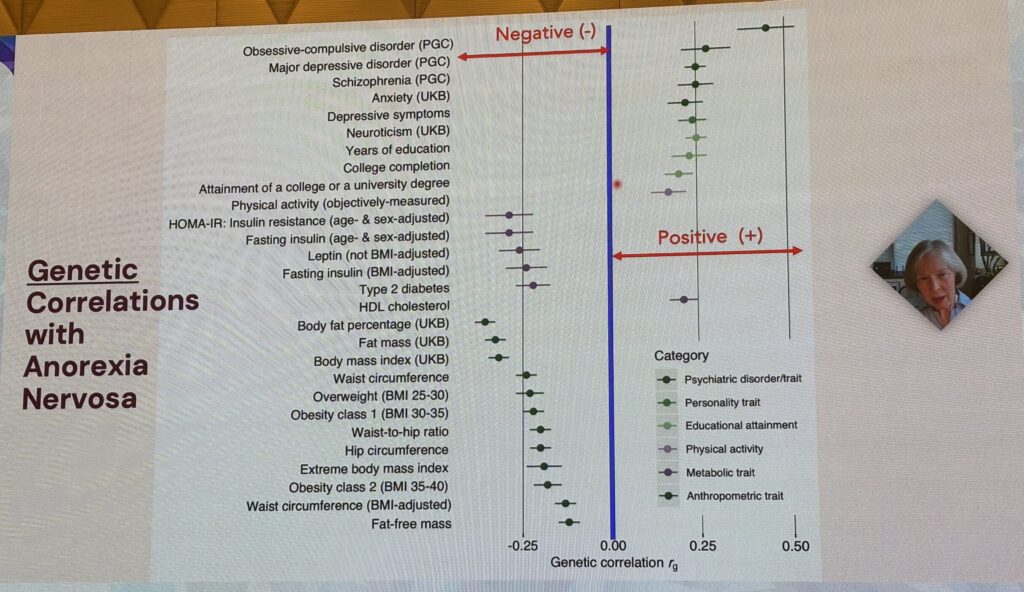

The GWAS study also shows certain interactions between genes. Genes that increase the risk of anorexia nervosa are also positively correlated with genes for other psychological disorders such as:

- OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorders)

- Depression

- Schizophrenia

- Anxiety

- Nevroses

But also – surprise! – genes that influence:

- the propensity to study for a long time

- the ability to obtain a higher education qualification

- interest in physical activity

On the other hand, the genes that put people at risk of anorexia nervosa are negatively correlated with other genes that influence metabolism, such as :

- Type 2 diabetes genes

- insulin resistance

- leptin (hormone regulating body fat)

- percentage of body fat

- BMI / overweight

- waist circumference

- waist-to-hip ratio

- hip circumference

- lean body mass

Anorexia nervosa is therefore a psychiatric AND metabolic disorder. This explains the increased risk of relapse associated to weight loss, but also the description of patients who went from ‘healthy’ to anorexic overnight, which could be explained by genetics that are more sensitive to even the mildest energy deficit.

If we consider that anorexia nervosa is a psychiatric AND metabolic illness, what does this mean, practically and in treatment?

- There is a genetic risk of anorexia nervosa, but there are also ‘protective’ genes.

- Treatments cannot solely focus on mental health; the metabolism and the body also need to be rehabilitated in order to recover.

- – Sometimes patients want to regain their weight but find it difficult to do so, or the treatments don’t give them enough time to reach a weight that is sufficient to suit their genetics needs. This sometimes leads to a cyclical series of recovery, followed by relapse, and so on, sometimes over several years…

Having said that, we need to remain extremely careful, because this is a complex field! Thousands of genes (protective or risk factors) and external factors (protective or risk factors) interact to create a unique combination for each patient! We have to work with each person’s unique combination, and scientists are working to create solutions to reduce/block the effects of genes, while psychology/psychiatry can work on the way we accept/react to external factors. We can also work at a societal level to minimise risk factors (weight stigma, obsession with the body, etc) and maximise protective factors.

Obviously, we’ll never be able to control all the factors perfectly, but here’s what this study implies:

- Genetics (and metabolism) must be considered in the causes and treatment of the disease.

- It is important to continue to de-stigmatise and remain factual when considering genetic risks (by asking about psychiatric history in the same way we would ask about breast cancer history, for example).

- This explains why, for some patients, recovery is a battle against their own biology! (sometimes difficult).

- Let’s not to fall into the trap of genetic ‘guilt’ or genetic ‘destiny’, because having a ‘risky’ heritage does not mean you will automatically have an ED.

In short: there is not ONE but MANY reasons patients develop an ED, intertwined in a way that is unique to each person.

It’s important to accept the inherent complexity of the genetic and environmental risks of ED, as well as the ‘protective’ genes and environmental factors – a bit like the hand of a pack of cards (see slide below)!

PS: a big thank you to my friend and psychologist extraordinaire Carine El Khazen, from ACPN, who has been organising this conference since 2019 and kindly invites me every year.